i.

I am reading Their Eyes Were Watching God for the first time. My momma and I are in a lil two person bookclub, and we chose to read Zora Neale Hurston, because we both realized it was a huge gap in our education. We finally got to the iconic and oft quoted line, where Hurston writes that the Black woman1 is “de mule of de world”.

Momma and I both cried when we discussed the implications.

My mother was a social worker for the city of New York. She eventually became the director of the wider NYC region, overseeing programs that advocated for the city’s forgotten and disenfranchised before she retired. My Mother Grand, a whirlwind of efficiency, juggled home health aide shifts with nights spent hunched over a typewriter, the rhythmic clack echoing the exhaustion in her eyes. And further back, Nanna Dear was a day worker who cleaned white women’s homes, and her mother toiled in fields under the relentless Southern sun. Generations of Black women, their labor relegated to the margins, undervalued, unseen, and in a straight line back to slavery.

For over a decade, I navigated office management and administration. I fetched coffee, washed dishes, cleared conference rooms, and protected fragile egos of people making three times my salary and contributing far less. After a while, I got promoted. The scope of my work increased, but so too did the expectation of emotional labor and the presentation of perfection.

Sometimes, the bullshit came with a side of emotional abuse, sexual harassment, or subtle manipulation that chipped away at my sense of self-worth. I remember the sting of being unironically called a “video vixen” in a meeting, the exhaustion from masking my true self, and the simmering anger of watching my labor go unrecognized.

"You're just so good with people," my old boss used to say, a patronizing pat on the head disguised as a compliment. He deadass used to pat me like a dog. "You're so eloquent!" While unspoken, the subtext hung heavy: "for a Black girl".

No matter what my title changed to, the truth of it was, I spent a decade employed as a corporate mammy.

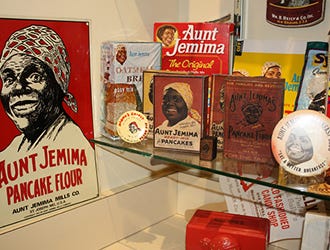

The "mammy" stereotype, purposefully created as propaganda to perpetuate the economic exploitation of Black women's labor in the post-emancipation labor market, remains a central obstacle to Black women's economic oppression and their attainment of soulwork.2

ii.

The dominant ideology of the slave era birthed several controlling images of Black womanhood, each designed to maintain our subordination.

The longest enduring of these ideologies is the Mammy.

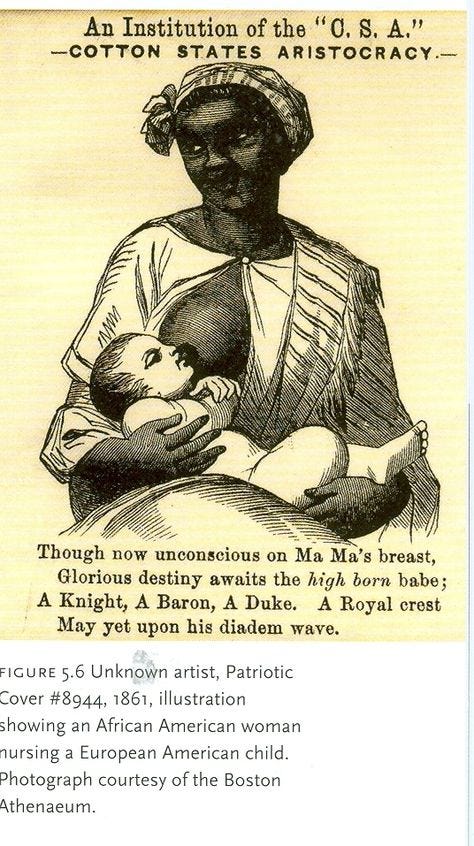

Catherine Clinton describes the Mammy caricature as an obese, coarse, maternal figure, willing to forgo the well-being of her own family in favor of maintaining a close bond with her white "family." Like all caricatures, Clinton argues, it contained a sliver of truth surrounded by a larger lie. While historical records mention enslaved women acting as assistants to plantation mistresses, these accounts are rare. Documents written by plantation owners in the first half-century after the American Revolution show very few such examples. The idea of the "Mammy" as a common figure managing white households only emerged after slavery ended. This suggests a deliberate creation by white Southerners in the years leading up to the Civil War, serving a dual purpose: downplaying the brutality of slavery and deflecting blame.

After WWII, economic restructuring led to our transition from domestic service to low-paid service sector jobs, clerical work, and other 'mammified' professions. Despite changes in job titles and specifics, the underlying economic exploitation persisted. The influx of Black women into the labor market made it possible for even middle-class white families to afford a Black domestic worker. The 'Mammy' stereotype served as a convenient fiction, depicting Black women as desexualized and submissive. This portrayal not only obscured the brutal realities of slavery but also eased the consciences of white women who hired Black women, despite the pervasive sexual violence inflicted on us by their husbands.3

"The mammy image represents the normative yardstick to evaluate all Black women's behavior… Mammy is the public face that whites expect Black women to assume for them." - Patricia Hill Collins

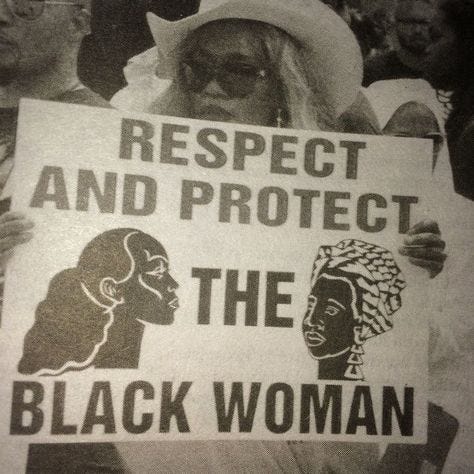

Hear me when I say this: The mammy stereotype was purposefully crafted to ensure our subordination and to justify our economic exploitation. The news and media portray Black women as naturally suited for subservient roles, masking the systemic racism and economic inequalities that forced us into such positions.

Today, we still face the burden of the "mammy" stereotype in executive roles. Contemporary mammies are expected to be completely fulfilled by and dedicated to our jobs. However, we are penalized if we don't appear consistently warm and nurturing at work. We are expected to suppress our needs for advancement, autonomy, and equality in favor of the demands of ego-driven managers. Employing us in "mammified" occupations reinforces the sense of racial superiority among white employers and encourages middle-class white women to identify more closely with the racial privilege afforded their husbands and sons.

This creates a cycle where our labor is undervalued and exploited, mirroring the experiences of our foremothers and our own experiences in corporate America. The mammy stereotype, though seemingly benign, has profound implications. It perpetuates a narrative that our primary value lies in our ability to serve others, often at the expense of our own well-being. This expectation is not only dehumanizing but also detrimental to our professional and personal growth.

Furthermore, the mammy stereotype intersects with other forms of discrimination, such as gender and class, compounding the challenges we face in the workplace. The expectation to be perpetually nurturing and self-sacrificing can lead to burnout and mental health issues, as we are often denied the same opportunities for advancement and recognition as our white counterparts. This intersectional oppression highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of how race, gender, and class shape our experiences in the workforce.

iii.

Black women during slavery were forced to not only endure the same backbreaking manual labor as the men4 but also become the nurturers, the emotional sponges – the invisible backbone of white society, our own households, and later, churches, voting booths, and even corporate offices. Our history has been weaponized, twisted into a justification for both the glass ceiling and the glass cliff. These micro and macro aggressions, like paper cuts, accumulate over time, leaving invisible scars.

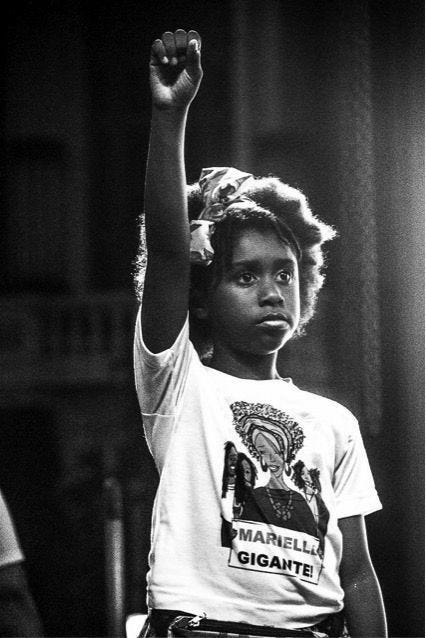

There's been a fire in my belly lately. A fire forged in the crucible of history. That fire refused to be extinguished by fluorescent lights and patronizing smiles. The turning point came when I finally saw myself reflected not in the office coffee pot, but in the unwavering eyes of the women who came before me. Their legacy wasn't about servitude; it was about resilience, about carving a path even when the odds were stacked against us.

So I quit my job. I’m trying a new thing.

The decision to leave corporate America was fraught with fear and uncertainty. The security of a steady paycheck was hard to relinquish, but the constant microaggressions and the pressure to conform honestly left me drained and pissed off and uninspired. It was a gradual realization that staying meant perpetuating a cycle of undervaluation and self-neglect. I had to honor the fire within me, a fire stoked by the strength of my foremothers.

Through soulwork,5 I have found empowerment.

I’m building my own path, one that values my skills, my intellect, and most importantly, my humanity. In this space, I am not bound by the limiting expectations of others. I am free to define my role, to pursue my passions, and to create a work environment that aligns with my values. The "Corporate Mammy" archetype might linger, a ghost in the sterile halls of power, but its hold on me is broken.

the actual quote says n*gger woman, but I don’t trust that kinda language to be read in good faith, tbh.

Soulwork refers to vocations aligned with our talents, desires, and efforts toward liberation. This is a concept I am fleshing out as part of my womanist scholarship.

This fear is further reflected in the enduring stereotype of the "Jezebel," the hypersexualized Black woman, used to justify the abuse and sterilization of Black women and femmes.

this is why the tradwife aesthetic annoys me. .. the aesthetic is literally racism. -_-

Soulwork is a Black feminist philosophy and framework I’m a scholar of that calls for aligning Black women’s vocation to their quest for wholeness, softness, and liberation.

you ate this right on up

With re this: Black women during slavery were forced to not only endure the same backbreaking manual labor as the men -it’s beyond truth, and honestly, we have never been afforded the space or grace to be women in this Country and let’s not pretend as if Malcolm X didn’t say it already: the Black Woman is the most hated animal on earth. All the BS is proof that we are vilified, set up, misused, denied every damn thing and to place icing on the stale ass cake, they hate what they created. Isn’t that some really funky 💩 ?