quick note. this is an essay that i wrote and released a few months ago, that i have since re-edited for clarity and brevity.

When I moved out of my Momma’s house, she gifted me with a small, prized skillet from her cast iron collection. It was a family heirloom, passed down from her own mother, my Mother Grand. Since then, Mommy has surprised me with a brand new dutch oven, but everyone knows – it’s better to get a pot that’s already been seasoned.

This tiny skillet, with its weathered edges and the patina of meals long past, rests heavy in my hands. It serves as a vessel of memory and tradition. Holding it, I feel both pride and a quiet sadness. Pride in the legacy of resourcefulness and care it represents, in the countless hands seasoning it with love and survival. Sadness because its heft also echoes the burdens borne by those same hands. A legacy shared by countless Black women throughout history. The humble iron pot has long been a symbol of empowerment and endurance and a testament to the indomitable spirit of Black women like me who have always had to balance resilience with restraint, labor with longing.

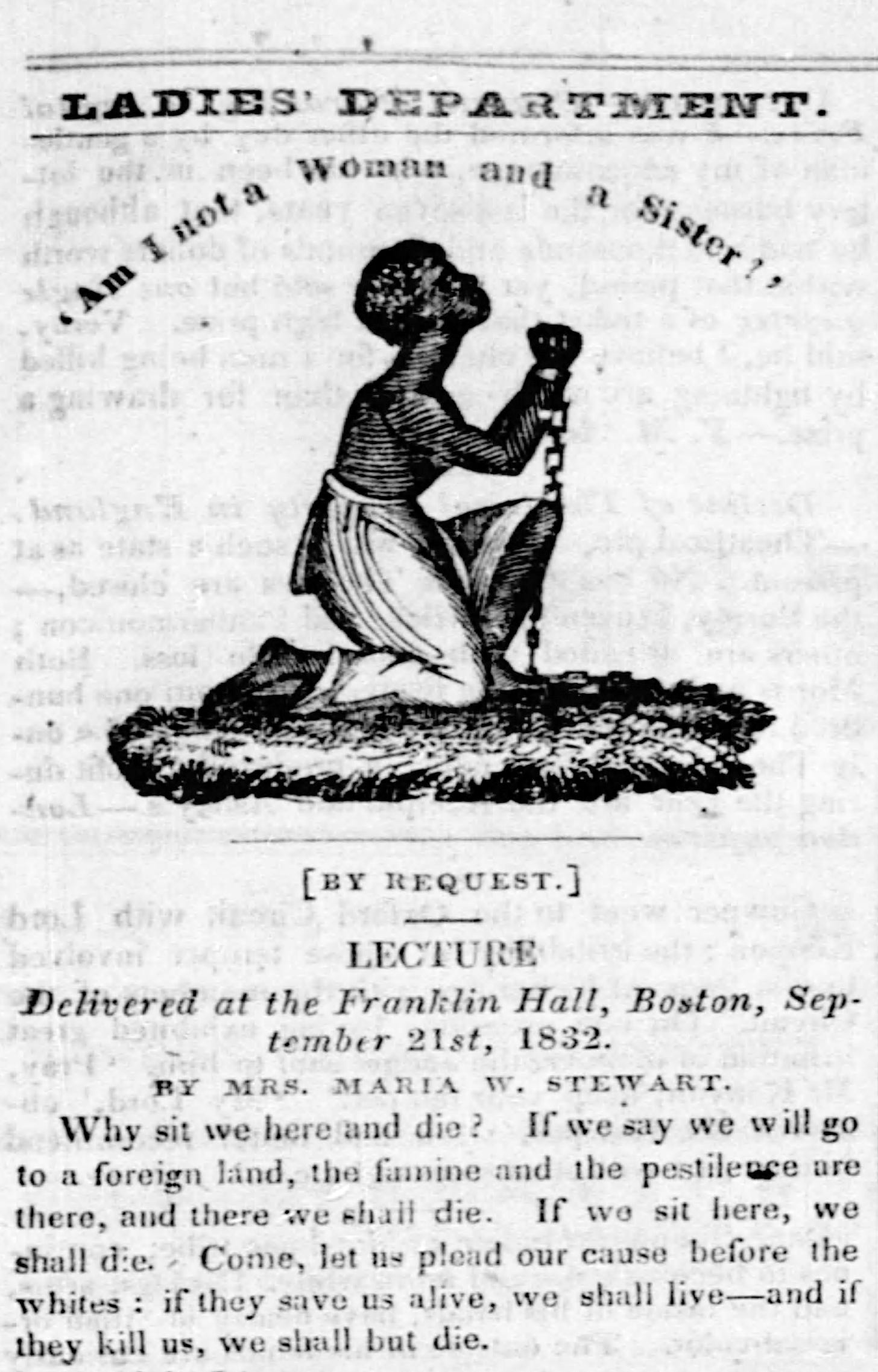

“How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?”

- Maria Stewart1

Maria Stewart’s rhetorical question resonates today like the clang of iron on iron. Born in Connecticut in 1803, Stewart emerged as a pioneering figure in the fight for racial and gender equality, utilizing her platform as one of the first American-born women of any race to address public audiences.

Stewart’s critique of 19th-century domesticity feels eerily prescient when I think of how Black women’s strength is consumed and commodified in the digital age. The platforms we navigate today are modern-day “iron pots,” promising connection and visibility while demanding we carry the weight of representation and perform resilience on cue. From viral videos that commodify Black joy to memes that trivialize Black pain, these modern-day vessels promise visibility but often extract more than they give. As I explored in my digital Blackface essay, the resilience of Black women, is consumed and commodified in ways that both demand our strength and dismiss our humanity.

Stewart’s rallying cry, “Possess the spirit of men, bold and enterprising, fearless and undaunted,” is no less urgent now than it was then. In this digital economy, what does it mean to “sue for your rights”? Perhaps it means reclaiming our narratives, shifting from being the subject of consumption to the architects of our own stories. It means resisting the urge to “perform” resilience and instead choosing rest, vulnerability, and joy as acts of defiance.

Stewart’s metaphor for societal constraint finds a spiritual echo in Lucille Clifton’s poem 'Rust,' where iron transforms from a burden to a sanctified witness of time and memory.

iii.

rust we dont like rust, it reminds us that we are dying. -Brett Singer are you saying that iron understands time is another name for God? that the rain-licked pot is holy? that the pan abandoned in the house is holy? are you saying that they are sanctified now, our girlhood skillets tarnishing in the kitchen? are you saying we only want to remember the heft of our mothers' handles, their ebony patience, their shine?

In "Rust," Clifton shifts the focus from external societal pressures to internal reflections on identity and the passage of time. The poem’s evocative imagery prompts us to reconsider our relationship with these everyday artifacts and the narratives they hold.

Clifton's sanctification of rust invites us to reimagine decay not as a marker of failure but as a testament to endurance. In a society obsessed with perfection and utility, the rain-licked pot becomes a sacred artifact, reminding us that resilience is beautiful, even when tarnished.

For Black women, rust is both a scar and a testament—a reminder of the weight we carry and the resilience we embody. This duality is central to Black feminist scholarship, and is often referred to as a dialectical relationship. Clifton asks us about our rust, where the pain of exploitation coexists with the strength of legacy. Her depiction of rust as both a mark of decay and a testament to resilience aligns with Stewart’s call to resist and overcome systemic oppression.

iv.

I am reminded of the personal journey that brought me to this moment—the journey of reclaiming the value of Black women's labor and rediscovering the power of my own voice. Receiving a tiny, rusted cast iron pan from my Momma was a simple act of inheritance, but it carried the weight of countless meals and memories. As I scrubbed away the rust and seasoned the pan anew, I was struck by how many layers of my own life had been rain-licked and rusted over.

Like many millennial Black women, I have faced my share of challenges—dropping out of college in the wake of sexual assault, navigating the complexities of corporate America, returning to college, and eventually starting my own consultancy. The road to empowerment has been fraught with obstacles, yet in the face of adversity, I have found strength in the resilience of my ancestors, the solidarity of my sisters, and the comfort of an old recipe.

To sanctify the iron pot is to honor its history while refusing to be defined by its burdens. It is to see ourselves not as vessels for others’ expectations but as carriers of our own narratives. In scrubbing away the rust, I reclaim not just a skillet but the power to season my life on my own terms. Reflecting on the rusty iron pot's journey from a symbol of constraint to one of enduring strength, I ask:

Are you saying that they we are sanctified now?

Love Y’all. Mean It. If you love me back, Buy Me A Book!

FURTHER READING

digital blackface

As we enter 2025, my word for the year is "gently forward." This phrase has become my mantra—a reminder to move through this year with purpose, but without haste. It’s a grounding call to lean into the work that is unfolding, acknowledging both the challenges and the opportunities that source continues to bring me to and through. This year, I’m deeply c…

https://thesoulworknewsletter.substack.com/p/heroes-are-people-too

all i have to give

“I am writing this first letter from bed. I lie here on my left side, peeking right hand from underneath the empty duvet to type. It is not practical, but it is necessary because I’m in pain again and depressed again, and this is all I have to give today.”- Cole Arthur Riley

Stewart, Maria W. Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality: The Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build. Edited by Marilyn Richardson, Oxford University Press, 1987.

Reading this as I have my cast iron dutch oven sitting on the stove. This is wonderful read. Thanks B!🌺