what they did to kiesha, they did to me

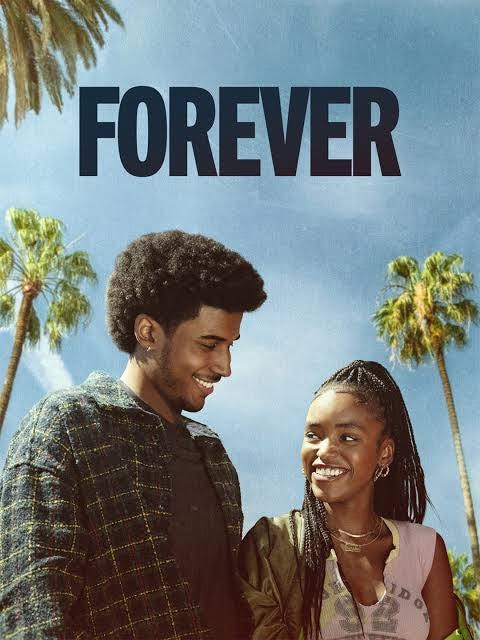

On Black Girlhood, Netflix's Forever, and the Myth of the Perfect Victim. This will contain spoilers.

I used to be a big Judy Blume girl. Coming-of-age stories hit different when you're actually coming of age, and Blume had a way of making the awkward, messy stuff feel important. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret helped me name questions I was just starting to ask about growing up. Forever gave me language for feelings I didn’t even know I was having yet—about sex, intimacy, wanting, and emotional independence. I still remember reading about Katherine and Michael as they fumbled their way through first love and awkward sex. It felt brave. Quiet, but brave.

The only caveat really, was that everybody was white.

Blume’s Forever was radical for its time. Published in 1975, it dared to talk openly about teen sex and birth control. But the story was also… soft. No one got truly hurt. No one was punished. Nobody’s life was destroyed. It was tender, even in its boldness. Katherine and Michael didn’t end up together, but they left the story intact. Changed, sure, but not broken.

Netflix’s Forever, reimagined by Mara Brock Akil and Regina King hits different. Set in 2018 Los Angeles, this version holds no such illusions. There is no cushion around Black girlhood. The stakes and costs for Keisha, our unambiguously Black protagonist, are heartbreakingly high.

And yes, I loved both book and show, but the reactions made me furious. In the story and out of it. Netflix’s Forever doesn’t have the luxury of innocence.

Neither did Keisha.

Keisha Clark is seventeen. Brilliant. A track star. Sweet but stubborn (she’s a Scorpio, so, duh). She’s just starting to find her footing again after a traumatic year: her popular ex-boyfriend sent a sextape of him and Keisha to a friend to win an argument. Without her consent. The video goes viral, and Keisha and her mother are run out of their neighborhood and away from her Howard scholarship.

The Netflix show is entirely centered around how the casual disregard for Keisha’s autonomy was weaponized, and how that interaction shaped her first love

The book asked, “What if a girl could choose sex without punishment?”

The show asks, “What happens when you’re punished before you even get to choose?”

What happens, it turns out, is that everyone blames Keisha.

Her mother’s first reaction is fury. Not at the boy. Not at the violation. At Keisha. There’s no hug. No comfort. No “we’ll figure this out.” Just disgust. Shame. The weight of respectability crashing down all at once. “You let that boy get a video of you?!” Keisha and her mother don’t speak for two days.

The other mothers—the PTA types from the school Keisha ran away from—aren’t much different. They cluck their tongues on the sidelines of baseball practice, and at the track meets. They warn their daughters to stay away. They “protect” their sons.

Even Justin’s mom, whose son is falling for Keisha in the way first love should feel, responds at first with alarm. She tells her son to be careful, to protect himself. As if Keisha is contagious. As if being harmed makes her a danger.

Through all this, only coming-of-age Justin is able to immediately and unwaveringly see the crime against Keisha for what it is. He stays steady when everyone else falters.

Keisha and Justin’s mom come around. They both voice the fact that they got it wrong the first time. But I’m sat with the reaction anyway.

There’s something especially devastating about being blamed by the people who look like you. The people who should know better. Black women who’ve been called fast before they even had breasts. Black mothers who know what it’s like to be preyed on, judged, and silenced. And still, STILL, they don’t extend the grace they never received. They put it all on Keisha. Because it’s easier to believe she brought it on herself than to admit how vulnerable they all still are.

And that’s the quiet violence Forever shows with unflinching clarity. Not just what happens when a girl is betrayed by a boy she trusted, but what happens when her whole community turns its back. When even the mothers shake their heads and whisper, She should’ve known better.

This Isn’t Just Keisha’s Story. It’s Mine Too.

When I was a freshman in high school, just 14, a senior boy told me he liked me. I didn’t think I was particularly desirable. I was bookish, “mannish”, eager to please. I thought being liked by someone older meant I was special. Mature. Seen.

He invited me into a stairwell.

And I went, not understanding what that invitation really meant.

I thought maybe he was going to kiss me. Maybe he just wanted to talk without the eyes of the cafeteria on us. I didn’t really know yet what it meant to be “fast.” How fast could I be? I was the last person I knew to have a boyfriend, or a first kiss. I didn’t know that being chosen by an older boy came with expectations, or that saying no might make things worse.

He asked me to give him head.

I refused.

So he hit me.

There are pieces of that day I still don’t have the language for. I should have bit his dick off — but .. I didn’t do anything. What I remember most clearly is the shift—the moment when I went from being a “nice girl” to “that girl.” He told people I was a whore. Said I did things I didn’t do. And everybody believed him. His word carried more weight than my silence.

I didn’t tell any adults.

Because what could they do? What would they do?

I had already learned that grownups (especially the ones who are supposed to protect you) can be more concerned with discipline than with justice. That when Black girls are hurt, people ask, What did she do to bring it on herself? That being a victim doesn’t earn you protection. It earns you suspicion. Reprimand. Pity at best. Punishment at worst.

So I kept quiet. I buried it. I carried it.

And like Keisha, I paid the price in my body and my spirit. I learned early that survival meant silence, and that “knowing better next time” was the only consolation anyone was willing to offer.

And there was certainly a next time.

The Myth of the Perfect Victim

There is a myth so many of us are raised with: that if we’re good enough, quiet enough, perfect enough, we’ll be safe. That harm only comes to girls who “bring it on themselves.” That the right outfit, the right tone, the right behavior will shield us. But that myth is a lie. And when it breaks, when harm still finds us, the people around us don’t blame the lie. They blame us.

In Forever, Keisha is punished for being sexual. For trusting someone. For having a body and desire and a moment of intimacy, even though the real betrayal wasn’t hers.

But we’ve seen this before. We are watching it play out, in real time, this very minute.

We see it with Blue Ivy Carter, as we adultify her on the red carpet. We see it with Cassie, as she bravely recounts being terrorized sexually, emotionally, physically, and financially by Diddy. And yet, the internet still asks, “Why didn’t she leave?”

Not “Why did he do this?”

Not “How do we protect women like her?”

Just that tired, weaponized question meant to shift blame back to the survivor.

It’s easier, apparently, to question a woman’s survival than to sit with the brutality of what she survived.

We see it with Halle Bailey, as we catch reaction videos to DDG being told theres a restraining order against him for slamming her head into a steering wheel. “He’s a father,” they said, as if fatherhood cancels out harm.

Art begets life. Life begets art.

In Forever, Keisha’s story is attempted to be held with tenderness. Justin never questions her worth because of the video. Her mother eventually demands justice. Justin’s mother thanks her son for reminding her that Keisha is a victim, and shows up for Keisha’s mother in solidarity.

Keisha overcomes. On screen, at least.

But.

The real-world reaction tells a different story.

Because the characters’ first instincts of shame, suspicion and abandonment linger. They mirror the real world too closely. It becomes a morality tale. A whispered warning passed from mother to daughter: Don’t be like her.

An ultimatum passed from father to son: Use her, or lose us.

Same script. Different cast.

And the question Forever quietly, devastatingly poses is this:

What kind of world turns on its daughters so fast?

As bell hooks once wrote, “Being oppressed means the absence of choices.” And for Black girls, those choices are denied long before we become women. We're not given room to mess up, to experiment, to explore. We’re denied girlhood, and then womanhood. We are denied softness. Denied the benefit of the doubt.

“Black girls don’t get to be children. We are born knowing how to survive.” - Brittney Cooper ; Eloquent Rage:

“The Black girl is often read as the problem, not the one in need of protection.” - Tamura Lomax ; Jezebel Unhinged

In Forever, Keisha tries. Lord knows she tries. She still goes to practice. Still shows up to school. Still protects her mother’s peace at the sake of her own. Still trying to hold her chin up while the world acts like she’s radioactive. But the truth is, the world is more comfortable with her survival than her suffering. They can’t hold her truth. They don't want her rage. They want her recovery, but only if it’s pretty. Only if it’s quiet.

Keisha is allowed to be loved only if she’s composed. Only if she swallows her shame and makes everyone else comfortable. If she survives beautifully. Except Justin. He loves her despite the messiness of their relationship. Despite the back and forth.

The title of both the book and the show is meant to imply permanence: of love, yes, but also of harm. Of expectations we never agreed to. The expectation to forgive before healing. To endure without breaking. To move on without being held. And to draw into stark contrast the ways in which teenagers (and those of us who don’t develop past teenagers) imply permanence on impermanent situations. And how those implications are often much more lasting than the situations we base them on.

What Would Loving Black Girls Look Like?

What if we believed Black girls who said “I am hurting”?

What if we didn’t punish Black girls for leaving, crying, screaming, or choosing ourselves?

What if we understood survival as messy and nonlinear…and still sacred?

To love Black girls is to let us be complicated. To hold space for our grief and still see our worth. To stop using shame as a shortcut to discipline. To stop treating harm as a lesson Black girls must learn before they can grow up to be women who shoulder shame like Jansports.

To love Black girls is to make room for our humanity. Our softness. Our fury. Our joy.

It’s to stop asking us to prove we’re worthy of care, and just give it freely.

Keisha’s story should never have to be about punishment. But it is because there is plenty of punishment inherent to Black girlhood.

Forever gave us a mirror. And it also gave us a choice. We can keep upholding the systems that shame and silence Black girls and the women they grow up to become. Or we can choose something else.

We can choose tenderness.

We can choose truth.

We can choose to believe her the first time.

Forever.

Love y’all. Mean it. If you love me back, Buy Me A Book!