my grandfather just died and i gotta process

(a liturgy for the orphaned and the ones left to pray)

i.

your father teaches you about god before you learn to distrust either of them. you are six, maybe seven, kneeling on a carpet patterned with geometric ghosts, your knees imprinting diamonds into your skin. his voice is a low hum, a bassline beneath the preacher’s shout. father god, he says, hands spread wide as the pews. you mimic him. your palms open like a promise. like an apology. you do not yet know that fathers can be both.

years later, you will pray into the static of a midday panic: lord, be a father to him, since his own is ash now. be a father to me, since mine is still learning how to live. the prayer reminds you of learning to use an abacus. reminds you of losses to be tallied.

ii.

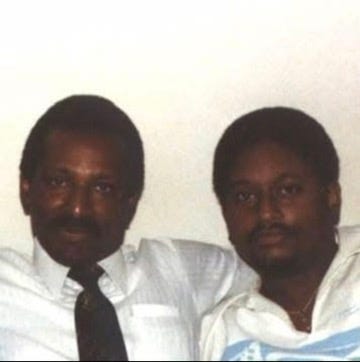

eldest children are born historians. we catalog the fractures. your father’s father died on a monday. you remember this only because your father’s voice cracked like cheap plaster when he told you. his brother (your uncle) died on a sunday. black men in your family only die on days the lord has claimed for himself. you wonder if this is a kind of blasphemy. a kind of surrender.

your father becomes an orphan at sixty-seven. you watch him age backward… suddenly small, suddenly soft. you want to hate him for this fragility. for a lot of things. you want to cradle him. you do neither. instead, you write essays about the weight of his love. about the way his voice shakes when he sings his father’s favorite hymn, the song a bridge between the living and the dead

iii.

the night your uncle dies, you ride with your father to identify the body. filthy march snow crusts the roads, the world hushed and gray as … well, death. daddy doesn’t let you actually see the body. he says decomposition has turned your uncle’s face into something unfamiliar. as you stand in the lobby of your uncle’s apartment building, your father makes a sound you’ve never heard. something like a howl. sharp as a siren. the kind that cracks the ice.

outside, the air bites your cheeks. you tilt your head back. the moon is a bone. your father howls again. you join him. two wolves mourning a third. two historians failing to rewrite the past.

later, you will call this shared grief. in the moment, it is simply air leaving two bodies at once.

iv.

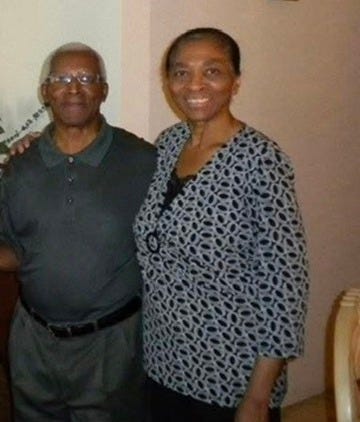

your grandfather dies at 6 a.m. pacific time. you are not there. you are never there. you are always there. time is an illusion, but grief is a clock. it ticks in your chest, in your grandfather’s voice, in the space between his last breath and your first memory of him.

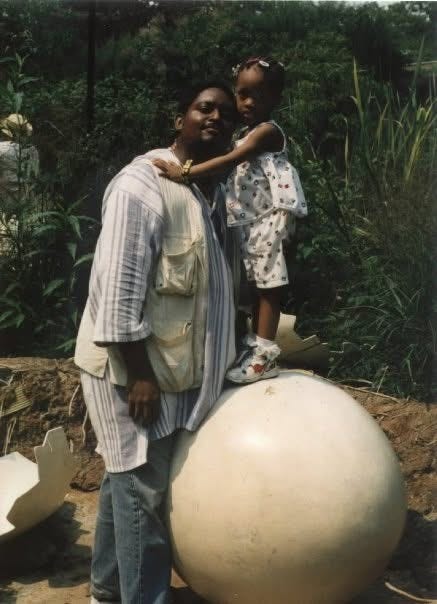

you know your grandfather through stories, birthday cards and phone calls, and one sticky summer: he let you eat popsicles for breakfast, but forbid you to read fantasy novels for the whole summer. he called you princess in a voice like gravel and honey, but he didn’t like to talk about grandma. a god-fearing man. healthy. but you were twelve. old enough to see the wound beneath his smile. old enough not to name it.

your father keeps his pocket watch. you keep the summer. the watch still ticks. the summer still melts.

v.

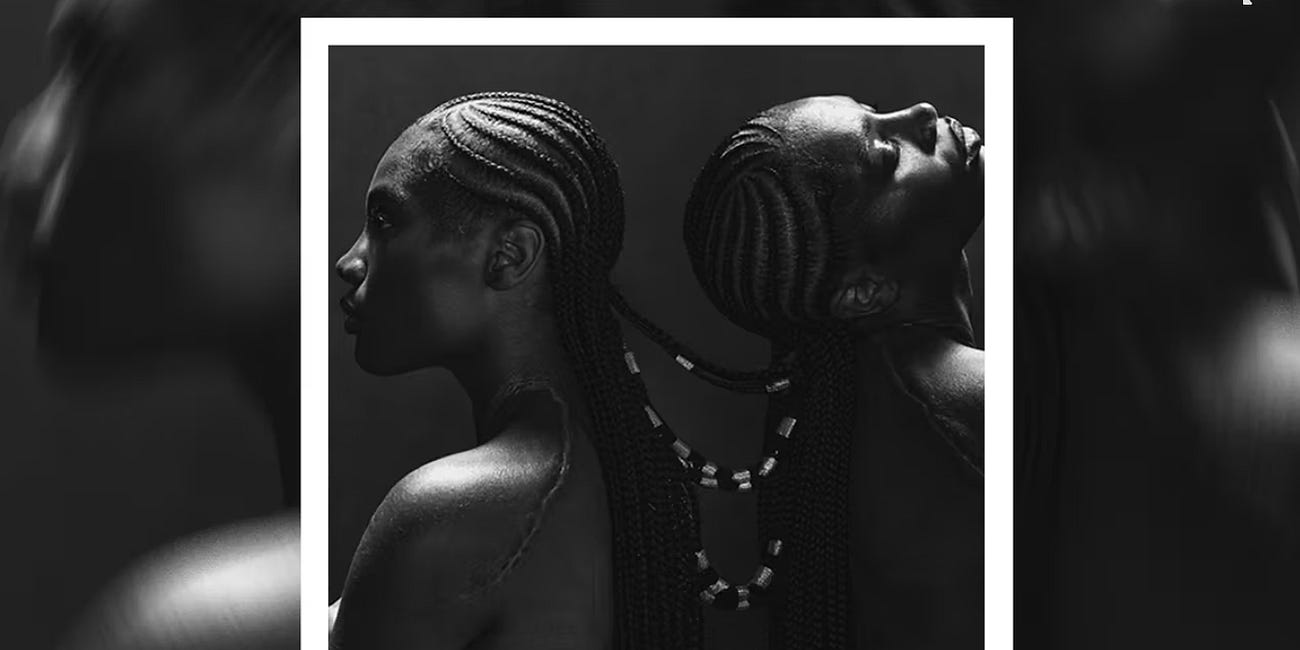

decolonizing faith is the work of unbraiding. you pluck the white god from your hair strand by strand. you burn the scraps in a bowl your grandmother left behind. but when your father gets sick, and almost dies, when the doctors shrug and say genetics, stress, the usual suspects, you remember:

you are four—the same age he was when his dad had to leave him the first time—and your father is gray. gray like the ice that night. gray like the static on the tv when the cartoons end. gray like the ash he will become. you do not know the words diabetic coma. you know only that your father is disappearing. that God is a thief. that survival is a language you learn too young.

and when you start to have nightmares about that night, you find yourself bargaining with a father-god again. old habits. older wounds.

a womanist once told you that black women pray in triplicate: ancestors, orisha, and the quiet rage of our own hands.

you add a fourth: father, whoever you are, fix what I cannot.

vi.

you are not a father. you are a daughter. you are the eldest. you are the family archivist. you are the keeper of unspoken things:

his father’s pocket watch, still ticking in a drawer. the summer he tried to teach you to drive, his foot slamming an invisible brake. slow down, girl. you didn’t.

you are both eldest children. you are both fluent in silence.

vii.

in the end, this is not an essay about fathers. it is an essay about the work of loving men who were never taught how to hold their own bones.

your father’s hands are calloused from building things that outlast him: houses, children, a legacy of absence. your hands are calloused from digging. from trying to unearth him.

you think of luisa from encanto, shoulders buckling under the weight of a family’s survival. you think of your father. you think of god. you think of the way black daughters are born already holding the world. already saying i can fix it, i can fix it, i can..

your father sends you a text. just a meme: a cartoon frog wearing a tie. you laugh. you cry. you do not reply.

the frog frowns. the lines that comprise him are janky. you think of all the ways black fathers say i love you without ever opening their mouths:

a meme sent at midnight. a hand on your forehead when you burn with fever. a hymn hummed through clenched teeth.

this, too, is a kind of prayer.

Rest in everloving peace. Horace A Smith. Granddady.

Love y’all. Mean it. If you love me back, Buy Me A Book!

-B

Further Reading:

Anxiety as Ancestor

Four years before Doechii won her Grammy, she dropped Anxiety on YouTube as part of her “COVEN MUSIC” series. It was a raw, unpolished manifesto for Black femmes who knew what it meant to hold fire in our throats and call it song.

My heart is with you, sis. I read these words with a prayer on my lips.

"eldest children are born historians. we catalog the fractures" I am taking this with me into my journal writing for the week.

This essay hurts so much because there are words here naming feelings I refuse to process… and now I must because I know you are sitting here with me. This is what writing is all about.